(The eighth of my nine posts about European culture from the 400s to the 1700s.)

If some Baroque music got a bit intricate, Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) can be seen as producing neoclassical Renaissance music — and, in a sense, as perfecting Renaissance music. Their music was marked by transparency, balance, and clarity.

Haydn, an Austrian Catholic, wrote all his best music after age 50, including, at age 66, The Creation. He wrote many happy songs and innovated with the sonata and the symphony with splendid results. His other great compositions include The Seven Last Words of Christ, The London Symphonies (which show his fullest reach), the delightful Clock Symphony No. 101, and Symphony No. 104.

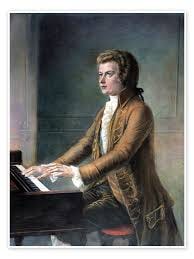

Which brings us to another Austrian Catholic, the musical genius Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. While composing, Mozart would see and hear whole and finished scores at a glance. His imagination opened to the riches of sound, his soul soared fearlessly, and an astonishingly abundant treasure of harmonies overflowed in brilliant perfection through his mind and fingers.

Mozart produced 626 compositions and he produced at least 100 masterpieces across seven genres of music: Masses, piano, chorale, chamber, symphonic, operatic, and concertante.

His compositions were harmonious, pure, complete, expressive, powerful, beautiful, enchanting, and sublime. For 250 years he has been renowned for his well-woven and memorable melodies, his precision, his depth, his maturity, and his innovative quality as a composer. And in the last decade of his life, Mozart composed music with extra cadence and chromatic harmony.

His best sacred music includes Adoramus Te (K. 327), Santa Maria Mater Dei (K. 273), and the haunting Laudate Dominum in the fourth of the Vesperae solemnes di confessore (K. 339).

His other great works include his Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, his Sonata in E minor for violin and piano (K. 304), his Quartet in D Major, his harmonious symphony No. 39 in E Flat (K. 543), his Sinfonia Concertante in E Flat (K. 364), his Piano Concerto No. 9 in E Flat (K. 271), his No. 20 in D Minor (K. 466), his Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor (K. 451), his Symphony No. 40 in G minor (K. 550), his highly memorable Divertimento No. 17 in D major, and his Concerto for Flute and Harp (K. 299).

Although he wrote tragic music such as the Adagio in D Major and the Requiem (completed by Franz Xaver Sussmayr), he rejuvenated — and still rejuvenates — our global culture with happiness and joy. There is his ever-popular joyful 1787 serenade A Little Night Music, and his joyful Night Serenade K. 239 for two orchestras is amusing all the way through.

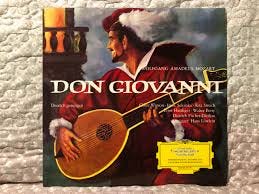

In much of the best of Mozart’s music, there is, beneath the suffering, some voluptuous reality. Mozart had the sense of humane joy shared by our most beloved comedians. His La finta semplice was a musical farce. His Cosi fan tutte was a comedy. And in Don Giovanni and the Marriage of Figaro, Mozart proved himself to be Shakespeare’s peer in comic theater.

With all three operas — Cosi fan tutte, Don Giovanni, and Figaro — Mozart collaborated with the Italian priest Lorenzo da Ponte (1741-1838), who wrote the librettos.

In Don Giovanni, even the death of the don is not tragic. Here we find Mozart’s power to lay out a comic surface, resolutely and scintillatingly contain it, and suggest something immense lying beneath it. There is wit in the comedy but also compassion. As in Shakespeare’s best comedies, Mozart shows that even through catastrophe, life is fun and we can still glory — as does his music — in triumphant and affirmative sentiments.

In Figaro, the romantic feelings are fully real to us, as in the best Shakespearean comedies. The positive climax is without irony. The whole opera is without cynicism. Guided by his own deep spirituality, Mozart shows us that happiness and love can be real.

These comedies of Mozart were works of immensity and scope. They moved along toward complete concord between human beings.

Most of all, as in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night and As You Like It, Mozart’s Don Giovanni and Figaro leave us knowing that we can realize both happiness and love in our lives. Could there be any more affirmative cultural statement that an artist can make?

Interesting about the Catholic side of Mozart. And good point about all the different elements of his contributions: sacred, comedic and tragic. I think one thing that makes geniuses geniuses is their ability to make quality contributions to many different "genres" as if it were their specialty all along. (Though some, like Dostoyevsky, were specialized exceptions)

While I am of the opinion that Shakespeare was a better tragedian than comedian (though you reminded me that I haven't read/seen As You Like It yet, so I might change my mind) the fact remains that he was as masterful comedy and tragicomedy as tragedy.

I have a question: Mozart and Shakespeare are but just a few who are geniuses but whom are known for tragedies especially. Do you think this is because tragedy is easier or harder than comedy? After all, comedy is often too dependent upon its own time. And yet it's because of this dependence that a timeless comedy is arguably better than a timeless tragedy.

I love Mozart. Best for times when you need something more soothing than Beethoven. Handel's water music is my first to go to for those moments. Thanks again for such a comprehensive and enlightening narratives.