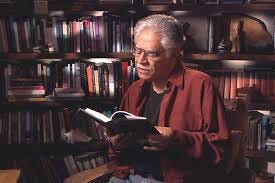

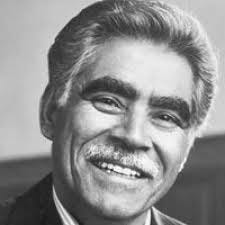

One of the biggest regrets of my life is that I never took a college course with the novelist Rudolfo Anaya, who was a professor of English at the University of New Mexico for decades beginning in 1974. In fact, I never even met the man. The closest I got was in 2017, when I showed up with a friend in UNM’s main library for a celebration of Anaya’s 80th birthday. His infirmities that day kept him from attending the party, so we videotaped ourselves, a couple dozen of us, singing happy birthday to him.

I’d be expected to have an affinity with Anaya on shared geography alone. I lived in two towns in northern New Mexico in elementary and middle school before moving to Albuquerque at age 13. Anaya, born in 1937, moved to the town of Santa Rosa as an infant and to Albuquerque at age 15.

But over time I’ve realized that my affinity with Anaya goes deeper than geography, strong as that bond is. He is an unabashedly spiritual writer, and it is his spirituality that most deeply resonates with me and to which I most powerfully respond.

I have read every book by and about him, many more than once. And I’ve found three of them both works of greatness and genius and personally meaningful to me — and thus three of my favorite novels of all time: Bless Me, Ultima as well as Tortuga and Jalamanta.

Schooled in Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, Pope, Whitman, Hemingway, Faulkner, Steinbeck, and Wolfe, after earning his bachelor’s degree in English at UNM in 1963 and his master’s five years later, Rudolfo Anaya found his own voice. “I used Anglo American writers as role models,” he later recalled. “But I really couldn’t get my act together until I left them behind.”

His voice, his act, his assumptions, his perspective, his worldview, his mythos – whatever you choose to call it, Anaya got in touch with a consciousness or a place or a space that is both mystical and primordial. And he did so while getting in touch with the depths of his own culture.

I’d call it the depths of the mythical Hispano-Native city that is called Aztlan. His books are filled with chants, guitars, dances, ballads, mysteries and fear of the unknown, life and death, occasional wailing and frightened cries, mysteries, anticipatory nighttime dreams, the supernatural including supernatural healings, and, most of all, spirituality.

A year after arriving in Albuquerque, at age 16, Rudolfo broke his neck while swimming. He floated in the water in the ditch, unable to move. “I saw my soul rising in the air, looking back on a reality I was leaving.” It took him a long time to recover from the paralysis, and his many months in the hospital with other sick, injured, and disabled boys became the basis of his beautiful, poignant, and moving novel Tortuga.

His runaway global bestseller – one of the best-known and best-loved Latino literary works of all time – was his 1972 novel Bless Me, Ultima. Anaya felt that this book, which he thought up in Spanish and wrote out in English, “captures the soul of our community”.

Interestingly, 1972 was also the year that Anaya earned his second master’s degree – in counseling. His books are never lacking in psychological insight.

In Bless Me, an adult man is remembering being a boy in 1940s northern New Mexico. Touchingly, brilliantly, Anaya recreates the scenes with the reactions of the boy, so our point of view feels like that of the 7-year-old Antonio Mares y Luna. “In childhood one undergoes primal experiences,” Anaya said, “and one responds to experience directly and intuitively.”

The question that animates Bless Me, Anaya said, is this: “How will Antonio ever find himself, truly see himself?” How will he, as a Latino boy in New Mexico, reach his authentic self, his true self, including developing his curiosity, sensitivity, and courage?

The answer: Through his normal and unusual experiences and through his mentorship by Ultima, an elder and a healer in the curandera tradition. She steps in, opens his eyes to his own world, and helps the boy discover the beauty and complexity in himself and in life.

Ultima understands far more than herbs. She understands people – their behavior, their psyches, their souls. In his spiritual encounter with Ultima, Antonio unleashes his great capacity for learning and becomes rooted in his identity.

There was such a figure in his community, it turns out, but Anaya was too young when she was still alive to remember her. Instead, while writing, “I heard a noise and turned to see the old woman dressed in black enter the room. This is how Ultima came to me.”

Was this actually the curandera from his community? “What are the characters in our stories but spirits who want their stories told? . . . I live in a spiritual place. New Mexico is home, stability, and history. It has the feel of my ancestors. Their spirits are here. They speak to me.”

Ultima opens Antonio’s eyes to the realities at the roots of his world. As Anaya said later, “The New World person is a person of synthesis, a person who is able to draw, in our case, on our Spanish roots and our Native indigenous roots and become a new person, become that Mestizo with a unique perspective . . . European Spaniard and American Native try to come to a kind of harmony (in yourself).”

This synthesis and balance get to something universal. We read novels, Anaya said, to understand ourselves better – “why we are here and what our purpose is in life . . . A good novel fills out our emotions and makes us more human, and it challenges us to think and to actively re-create our lives . . . What all of us want to have inside, a certain peace of mind, a certain harmonious relationship to our fellow human beings and to the universe.”

Anaya knew that he was drawing something universal from Native cultures. “When I turned more toward Native American mythology, I began to see that there are these points of reference that world myths have, that somehow speak to the center of our being, and connect us – to other people, to the myth, to the story, and beyond that to the historic process, to the communal group.”

Spirituality was the sole focus of Anaya’s 1996 novel Jalamanta: A Message from the Desert. Here we encounter what is almost certainly Anaya’s own spiritual approach to life.

Here Anaya teaches us to choose to follow the Path of the Sun, to allow the Sun to fill our soul, and then to walk in the Path. The Sun reflects the universal Light that fills the universe. The Sun fills us with Light. We bathe in the Light. The Sun heals us. While our mind separates things, our true soul sets aside the veils as it senses the wider community. The essence of the soul is love, love is union, and love is the Holy Grail.

The free soul, the pure soul, feels connected with other souls and with the Universal Spirit. It sees itself in the souls of others. Their soul reflects us in them, and our soul reflects them in us. As our soul responds to truth, it resonates more and more with the souls of other people.

To Anaya, the universe was created by Divine Love. Our soul yearns for the Love and Light. The Light creates the dance of life and each soul is a creative energy. When we admit the Light, when we trust the Light, we act well toward our neighbors. We live with noble purpose as our soul visualizes its potential in the ongoing dance of life.

In the Latino-Native tradition, there is the ideal of the inocente. “Inocentes sense that Divine spark that illuminates the simplest acts of the day. The inocentes know this intuitively, for that is how they live, that is how they are most alive.”

Anaya at his best was an inocente. He talked of how he tried to stay attentive and to keep his soul filled with light every day. “Each morning I look at the rising sun and give thanks. I offer a blessing at sunrise – I bless all of life.”

Anaya called out – and continues to call out – to the people of his ethnicity, his race. “The Mexican American community has to find ways of breaking out of its bondage, its paralysis.”

And Anaya continues to call out to each of us. He calls us to affirm our humanity, to stay in touch with the Tree of Life – our roots, our community, our collective memory – while defining our unique self and declaring our independent consciousness and identity. And he calls us to walk up the road of life with a smile of wonder, to take command of our destiny, and to move forward to fulfill our potential.

What more can we ask for from a writer?

Thank you for this wonderful essay Mike. I love Anaya and now I am going to dust off some of his books I have and read them again. Un abrazo fuerte, Francisco.

A wonderful appreciation MIke. I can't wait to read more from Anaya now.